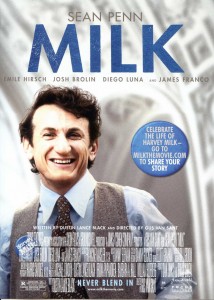

Milk Movie Poster

I wonder if years from now I will be more taken with where I saw Milk — in a weary, mostly empty theater in Tallahassee, sitting amid a small clutch of Southern gays and liberals (going at least by their Birkenstocks and hybrid cars) — than that I saw it at all.

Milk is a strong biopic, respectfully (but not too respectfully) crafted. Because I grew up in San Francisco and lived in the Castro district in in the late 1970s, a place and time where most of the movie takes place, and because I was at least a bystander for some of the public events, and knew what the principals looked like and in some cases how they spoke and moved, I have a standard for “being there” few movies could hope to match.

Yet Milk not only met and often exceeded my expectations but moved beyond the usual biopic you-are-there territory, doing justice to the idea of a portrait as a reflection of us all.

Sean Penn is distinctly Harvey, all geeky elbows and mobile, comical face (I have a poster of Harvey in a clown costume, a role he loved and a job he sometimes held). It is a remarkable performance, one which proves the phrase, “he disappeared into his role,” and if Penn does not get an Oscar, I give up on the Academy for good.

Scott Smith was off-stage to me by the time I moved to the Castro, so I accepted James Franco without question; he certainly evolves well from a gay hippie sprite to a sadder, wiser ex-lover tired of playing second fiddle to Milk’s political cravings. However, though Emile Hirsch captures Cleve’s mop-top and puckish face, and the right words came out of Hirsch’s mouth, with all that skipping and arm-flopping, Hirsch is far more gamine than Cleve Jones as I remember him from that era, with all apologies for the rough red pen of memory. (Perhaps, among an movie-set army of Castro Clones, Cleve was recreated as the token twink.) Still, it is a brave person who agrees to have his fashion choices from the 1970s recreated with unnerving fidelity, and Hirsch’s impossibly-large glasses and tight tees were spot-on.

Alison Pill works all right for me as Ann Kronenberg, but only because she was someone I do not remember seeing close up; but I still wonder if Pill’s pudding-face captures the toughness of a biker chick who was one of very few females in a power role in the testosterone-charged gay political era of the late 1970s in San Francisco. Ann “likes women,” but is never seen with one, and when she begins working in Supervisor Milk’s office, Ann makes an unexplained shift from jeans and leather jackets to the tight sweaters and long skirts of the Mr. Goodbar era (even as Cleve is told to wear what makes him comfortable) — a point that could have been played out a beat longer, with clarification. Yet Supervisor Dan White is played with unnerving fidelity by Josh Brolin, who carefully does not go over the top and just as carefully does not hog the screen, while Harvey’s boyfriend Jack Lira, played by Diego Luna, could be any politician’s uncomfortably unstable love interest.

I had hoped for more views of the Castro neighborhood itself, but that’s because I’m greedy; any more, and the focus on Harvey and crew would have been muddled by scenery. It’s remarkable how perfectly the set of Milk recreates a vibrant, sui generis neighborhood I have known incidentally since childhood and closely as a young adult, a place I go back to again and again both in the real world and in my mind. I think every important conversation I had in my early twenties took place either while I was going door-to-door with my friend David on behalf of BACABI, the local campaign effort to defeat the Briggs Initiative, or sitting in Cafe Flore on Market Street, drinking then-exotic cappuchinos and watching the world strut by in its tight leather chaps.

The public events recorded in Milk proceed without any surprise for me, comprised as they are of rallies, marches, campaigns, and other crowd scenes I either participated in or had related to me second-hand the day after, often while standing at a bus stop at 18th and Castro. But the movie never dragged, absorbing me in every period detail, every tension among Harvey and his lovers, every new character arriving at just the right moment, every politically-fraught moment teased out on the screen for just long enough and no longer.

A meeting between Harvey and John Briggs in an abandoned lot — where Briggs refuses to shakes Harvey’s hand, and Harvey continues negotiating without losing a beat — was both new history to me and proof of Harvey’s surreal ability to set aside anger and see opportunity, as he commits Briggs to debates that though they appeared on Briggs-friendly ground had the opposite effect statewide.

(The audience was still as a winter night in a scene where Harvey fumes that the proposed “No on 6” campaign material doesn’t once mention the word “gay.” ‘Not frightening the horses’ was the failed strategy of California’s campaign to defeat Proposition 8. Some have wished Milk had debuted several weeks earlier; with no disrespect to those involved in the movie project, just mere hindsight, I have concluded Milk was a year late.)

Milk also captures beautifully how Harvey served time and again as the balm of Gilead, refocusing an angry crowd on his themes of hope and change. This was no mere parlor trick; it was a gift crucial to Harvey’s leadership, and the stirred, fuming crowds who settle down to chant and clap along with Harvey stand in for not just the determined gay body politic of that time, but the entire, and entirely malleable, human race. Harvey, as imperfect as the rest of us, had a supremely dangerous gift, and he used it nearly every time for good.

Biopics, like all good nonfiction, concoct their alchemy from the true artifacts of the known world, and must skilfully dance around not just real people and events, who often messily refuse to fit their narratives into tidy Aristotelian boxes, but the accumulated truths that occur after the biopic’s events. The headiness of 1970s gay San Francisco had its own powerful letdown in the arrival of AIDS in the early 1980s, and the movie manages to delicately hint at the future without introducing maudlin distractions. There is just the right prefiguring in the casual references to bathhouses, casual sex (which as memory serves was hardly the exclusive provenance of gay men), and, in an early scene cut sharp as a diamond, a speech from Harvey to Cleve about a life filled with many lovers and friends.

Milk concludes with a small, deeply satisfying “return,” repeating a scene from the beginning between Scott and Harvey. In the hands of someone other than Gus Van Sant (a director who in Elephant managed to make teen-killers sympathetic) the return might have been superfluous or even intrusively annoying, but when the moment arrived, I sighed with that sense of rightness and inevitability that only a good ending can bring.

Huffington Post put a spoiler alert around part of the ending of Milk, adding a “whodunit” angle to the movie that initially baffled me, given that Milk smartly begins with the fact of Harvey’s murder, ensuring that the movie’s trajectory is toward Harvey’s life, not his death.

But though uber-reviewers such as A.O. Scott assume everyone knows the finer-grained details of Harvey’s murder (a faint whisper of Pauline Kael not knowing anyone who voted for Nixon), I will respect Huff Post’s spoiler except to say the ending has to do with Supervisor Dan White — not just what he did, but the frightening way he did it. I had forgotten that the murder of Harvey and the man my parents called “Gorgeous George” Moscone (a dapper, smart politico played beautifully and with silken restraint by Victor Garber) was a peculiar, distant event to many in my own country, though it was as close and real to me as my own hands.

I was standing in the records-room of San Francisco Juvenile Court, sorting file cards by the window, when we heard this news, and a co-worker, pleased with jackass self, said, “See, Karen, they got another one.” The next I knew, I was in my rented room and on the phone; sad, anxious hours slid by without memory, and then I was in the candlelit march from the Castro to City Hall that in Milk both stands in for the arc of Harvey’s achievement and rightly concludes the film.

A time long ago and far away; and now, with Milk, risen again, in all of its wit, hope, pain, and beauty.

Can’t say enough about how wonderful this flick is. Penn (not my fav) nails it and the production is almost flawless.

However I was disappointed in the lack of women in the movie. I know that we were invisible, and still are to some extent, in the community but I could count on one hand the number of dykes in the movie.

Then I rented an equally wonderful documentary, The Times of Harvey Milk and saw Sally Gearhart and a few others that really could have been included in Milk.

But, still, it’s a “must see”.

I agree with Pam. It is also great to read your thoughts on the film, and on what it was like to have been there, Karen. Thank you so much for sharing this with all of the folks who weren’t able to be in The City in the 1970s.

Kim and I saw “Milk” the night it opened in Grand Rapids, with fewer than 20 people in the audience for the first show. I had rented The Times of Harvey Milk the previous day, so I knew what to expect – and, like you and Pam, I felt that Sean Penn was practically channeling Harvey Milk. His performance was beautiful. [Sadly, the Academy Award will probably go to Mickey Rourke, for playing a version of himself.] At the end of the film, I sat still and cried a little, and wondered what things might have been different if Milk had not been assassinated.

On the other hand, seeing the film reinforced my decision to come out of the closet. It was certainly the right thing to do.

Karen: I was an eight-year-old in Benicia in November 1978, and I still vividly remember Leo Ryan being gunned down, the Jonestown mass suicide, and George Moscone and Harvey Milk being assassinated, all happening within about a week, and just a few months after my parents divorced. Thirty years later, and I have never shaken that feeling of the world being a dangerous place that could come to an end at any time.

Karen, you won me over with this post and I am subscribing to your blog. I haven’t seen Milk yet but intend to. The trailers set off triggers but yes, I will go there and revisit that time. I was 21 in 1978, newly graduated from a prestigious school of journalism, idealistic and ready to take on the world, (or at least my parents) and broaden narrow mindsets. I grew up amid assasinations of our best and brightest hopes for change but was not prepared for the sacrifice of Moscone and Milk and the twinkie. Needless to say, I haven’t had a twinkie since…