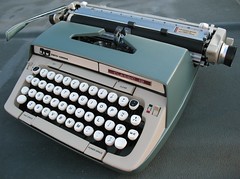

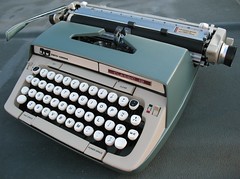

Smith-Corona Classic 12, by Flickr user mpclemens

I promised that post-ALA I’d sketch up some technology trends I have observed, to complement the trendsetting discussions held elsewhere, such as LITA’s Top Tech Trends.

“The Big Shift.” I had a number of mini-conversations with respected colleagues where we agreed that the adoption of ebooks and the shift from DVD to streaming was happening faster than even we anticipated. Netflix now streams more than it rents, the Kindle is no longer a novelty and has serious competition, and there are multiple publishing streams.

I am personally considering republishing my published essays as a Kindle or Google Books collection. (I remember proposing this to an agent in Florida in 2009, who stared at me uncomprehendingly.)

For me, the Big Shift also has a hugely literal component: the shifting of books from libraries to offsite storage, and the shifting of library space use from housing low-use, just-in-case print materials to supporting individual and community information behaviors, pedagogical, creative, entertainment-oriented, exploratory, etc.

The “literal shift” is being enabled by the print repository movement, which is finally trickling into mainstream higher-ed awareness; it even made the Chronicle of Higher Ed last week. In anticipation of the ability to move materials offsite, I’ve been moving the pieces on this board by having our library join OCLC, implementing interlibrary loan (yes, I know, party like it’s 1977… we’re behind on our developmental markers), and implementing OCLC’s Navigator and express-van delivery for our Camino service (ok, now we’re ahead of most of you). That, and oodles and oodles of grim sloggy work, a lot of it still ahead of us, to ensure that all of our books are in OCLC.

Oh, and when anyone asks me about compact shelving, I reply, repositories. A far better investment. The print we keep will be display-worthy, the sort of books to showcase on bookstore-style gondolas with handsome endcap treatment, not to stuff into ponderous, expensive “compact” [sic] shelving with all the appeal of prison housing.

I’ve been talking about regional repositories in general, and WEST specifically, ever since I spent two weeks traveling through Australia in 2008 with repository guru Lizanne Payne.

Listening to her, I had that same “ah hah” moment I’ve had a few other times in my library career, like the first time I brought up Mosaic on my home computer and got the TCP-IP stack to work, and when a huge NASA image of Jupiter appeared on my screen I was so excited I had to leave the house and drive for an hour just to calm down. I haven’t shouted “squee” over repositories (not the same sex appeal), but as noted above, I’m getting ready for them.

I’m now going to let you in on a dirty little secret. I was asked the other day by a library student why I would shift materials offsite rather than rigorously weed them first. Yes, we do weeding, but it’s a bare smidgen compared to the size of the collection, even after weeding 6,000 volumes through last May and a few more hundred since then.

The answer is I will never have enough expert labor to weed our collection top to bottom, let alone do the sort of collection analysis to determine if I’m taking responsible “last copy” actions with our materials. I run a university library with 4.0 FTE, forcryinoutloud. Even if our workforce doubled, I wouldn’t direct its efforts in that direction, not when I could wrinkle my nose, Elizabeth-Montgomery-style, and make the books move offsite (well, it may take a teensy more than that).

Yes, I am foisting hard decisions on another generation. But I write this so that anyone studying the repository movement knows the reasoning and motivations of at least one library with skin in this game.

Wifi saturation. Our institutions cannot keep up with the thirst for wifi. I have observed a mini-trend where universities are reverting to wired usage wherever connectivity is critical (see notes to this Flickr trip report for UC Merced). As Donald Barclay noted in MPOW’s visit to Merced, people are wandering around armed with multiple mobile devices, many of which are wifi-enabled, many of which are always on, and which are sucking ever-more-intensive webpages (my language, not his…).

Elsewhere people have commented on the surge in tablet use; Jason Griffey noted in a post-midwinter webinar that the Consumer Electronics Show featured over 40 tablets. The New York Times recently reported on the surge of e-readers by young adults. In addition to using actual data (“At HarperCollins, for example, e-books made up 25 percent of all young-adult sales in January, up from about 6 percent a year before”), this article was notable for not even attempting to debunk the trend in ebook readers, which assuredly would have happened ten or even three years ago.

My hunch, down the line (and I doubt this is a unique observation), is that we will all end up being our own personal networks; cellular speeds or other technologies will allow us self-contained connectivity. The person with an iPad with 3G is essentially a network unto herself.

I recently traveled shoulder-to-shoulder with Alison Head (of Project Information Literacy fame), and we were a walking ad for iPad + 3G; we’d be in an airport and she’d be surfing and I’d be sitting there, wishing I could get online and begging to use her IPad. (My observation: an iPad with wifi is a toy; an iPad with 3G is a tool.)

Laptops. Yeah, you’re thinking, what’s new about that? First, and simply, is the trend line, relentlessly moving upward. We surveyed our incoming freshmen and found that 89% have laptops–a surprisingly high figure, based on our anecdotal observations.

The assumption has been that our students are “poor” and don’t have laptops. What’s going on, I suspect, is infrastructure and workflow: the need for electrical power, ubiquitous (and always-reliable, ever-faster) wifi; and the logistics of toting a “mobile device” for 14 hours a day, to and from work, school, and so forth–lugging it, protecting it, worrying about where to secure it (I’ve seen a number of libraries that offer lockers, some with power built-in; Loyola Marymount, for example). We have wifi, but the demand on it is great; and students are now using resources that simply aren’t useful without network connectivity.

Another assumption is that laptops are still viewed as mobile devices. Compared to the computer in Desk Set, yes. Compared to tablets such as iPads, they now seem pretty bulky. I wonder if laptops are the new PCs (or even the new Smith Coronas–remember going off to school with your typewriter)?

In any event, for the people who are carrying their Smith Coronas with them (and when we cleaned the processing room I found a “portable” microfilm reader; how cool is that?) what I am seeing on many site visits to libraries academic and otherwise (including a whirlwind tour to Lafayette Public a week or so ago) is a shift from providing computers to providing ancillary support for mobile technology: at minimum, comfortable study areas and desks with power, and large monitors with VGA cables (for MPOW we’re pondering dual-VGA cables, labeled Mac and PC, with a MacBook VGA adapter taped to one cable). A variety of tables, a variety of seating, a variety of study rooms, and plenty of food.

Most libraries are still providing computers, and for many public libraries they are necessary lifeline services, but for academic libraries and public libraries where the population is more affluent, the days when every available table and network drop was occupied by a library-provided computer — and when the bulk of purchasing was devoted to these computers — is a ship that has sailed.

I should end this post with a flourish, but I’ll just have to wrinkle my nose and post it (Darren and Tabitha are calling).