Last week the ever-interesting Barbara Fister observed over on Inside Higher Ed,

People are beginning to notice that big publishers are not really all that interested in authors or readers; they are interested in consolidating control of distribution channels so that the only participants in culture are creators who work for little or nothing and consumers who can only play if they can pay.

Barbara elegantly collapses into one sentence the last several years of the ebook wars and, even more importantly, identifies all stakeholders in the reading ecology: not just publishers and libraries, but authors and readers.

The Growing Crisis

Over the last year or so, there has been spluttering (sometimes from me) at individual publishers such as HarperCollins (they of “26 checkout” fame), distributor-packagers such as Overdrive, and of course, the idiot library administrators who sign contracts they obviously haven’t read, or they would never have entered into those agreements, right? (That spluttering definitely didn’t come from me, being one of those administrators.)

But Barbara is pointing out that while the problem has many moving parts, the entire reading ecology is at risk; we are, in her terms, in an “apocalypse.” It is really nothing less than an outright assault on fair use; the publishing-industrial complex won’t be happy until readers are paying, not just by the title, but by the page-turn.

Barbara and I have an interesting convergence: we are both librarians-authors-readers (except she can write entire books, while my attention span ends at the essay). By author, I mean (full disclosure: HUSTLE AHEAD!) non-industry writing, such as the forthcoming The Cassoulet Saved Our Marriage (Roost Books, Fall, 2012; edited by Lisa Catherine Harper and Caroline Grant), in which you will find my revised and republished essay, “Still Life on the Half-Shell” (first published in Gastronomica) about oysters, the locavore movement, and how I came to terms with life in Tallahassee. My essay includes exquisitely clear instructions on eating oysters Southern-style (complete with a photograph), making Cassoulet an obvious “must buy” for all library collections.

But my point isn’t about whether I am expecting to make a living from essays such as “Half-Shell.” My day job is my income; I can’t even remember if I am getting a small one-time payment, though I had such good editorial input from Lisa and Caroline that the revision process was its own mini-post-grad workshop, and I have a food essay floating out there that is significantly better for the lessons learned for “Half-Shell.”

My point is that it’s important, both ethically and strategically, for advocates of the right to read to understand that creators should have the option and the right to make a living from their creations, and that our advocacy, right now, at this moment in history, is crucial to ensure that right.

It’s also the reader’s right to support creators, which they can do either directly (buy my book!) or indirectly (fund libraries, and they will buy my book). Some of us in society will “buy” books, by way of funding libraries, that we never read ourselves or that we choose to purchase on our own, but we understand that the town pump benefits everyone — a take on the world that is less popular in certain circles, but only underscores our value to society.

What happened?

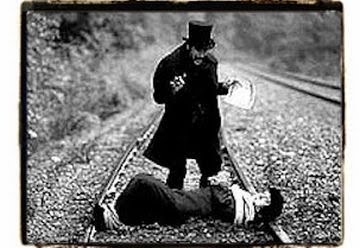

In the past, the writer-publisher-library-reader model had a modicum of equanimity. It is now obvious that the nature of the technology — the printed book — largely regulated that equanimity. All of us in the reading ecology — librarians, authors, repackagers, readers — are tied to the tracks by the Brobdingnagian power wielded by the highly consolidated publisher-industrial complex that is then magnified a thousand-fold by the conveniently elastic, virtual nature of digital publishing.

As Steve Lawson observes, publishers can get away with limiting access, so they limit it. As Kate Sheehan points out in a comment on her own post, publishers can cut us out of the conversation, so they cut us out. Though it has been proven time and again that library reading boosts individual book sales, that’s not good enough for for the publisher-industrial complex. They smell an opportunity, and their greed is overwhelming any vestige of decency or sense of social fairness.

Deep down, the publishing-industrial complex will not be satisfied until they can do away with those pesky librarians, they who broker reading as a public good, champion the right to read, and advocate for equitable access. Penguin invoked the term “friction,” in reference to the ease of checking out books; but I see the real “friction” as the Bonus Army of librarians, authors, and readers who are speaking truth to power. How convenient it would be if we were starved out of the reading ecology.

We’re also back to my ancient observation about Google: “don’t be evil” does not translate into “do be good.”

What is to be done?

I’m not a fan of…

- Dwelling at length on the supposed sins of any one publisher or redistributor; this isn’t just HarperCollins, Penguin, the other publishers who won’t even deal with Overdrive, or Overdrive. It’s bigger than that. (Note: I lay aside the Elsevier boycott, which works for other reasons, in a different situation and a different reading ecology.)

- Singling out individual libraries over their Overdrive contracts.

- Assuming Dilbertesquian cluelessness on the part of librarians struggling to provide ebooks to readers.

- Arguing that Information Wants To Be Free and therefore creators should work for free and make a living some other way. That’s not only naive, it leaves just one profiteer in the equation: publishers. (Again, this relates to the for-profit book industry. Scholarly publishing also relies on slave labor to line publishers’ purses — which is the point of the Elsevier boycott — but it’s a different ecology. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch, but sometimes it’s hard to point to the money on the table.)

- Assuming “they” will solve the problem. Much as I appreciate ALA going to meet with big publishers, one of those publishers, Penguin, subsequently thumbed its beak at the reading ecology, withdrawing from Overdrive with a timing that can only be labeled impertinent.

- Indulging in magical thinking; the clock isn’t rolling backwards, and ebooks are here to stay.

I do think we need to…

- Recognize this crisis as a reading-ecology problem and a fight for the right to read, not just a public-library problem. It doesn’t matter that this has primarily been about Overdrive, whose customer base is overwhelmingly public libraries (though Overdrive has higher-ed customers, including Yale, Pitt, and my tiny library). We’re all part of the reading ecology.

- Inform and engage our stakeholders, such as the Free Library of Philadelphia is doing., and as Peter Brantley did through Publishers Weekly, though I was a little uncomfortable with his portrayal of public libraries. They aren’t all urban catchbasins, and strategically, we need the large middle-class voting base to understand their stake in this crisis.

- Study the structure of our reading ecology and have economists and other strategists propose workable solutions. I know there has been talk about “buying” Overdrive, but even if it were for sale, would acquiring the repackager/redistributor solve anything? We need some serious theory at work for us. This is made even more challenging because library “science” is an iffy discipline at best.

I wish I had more ideas, but I solicit yours.

Posted on this day, other years:

- Heading to Code4Lib, Prepping for Evergreen 2009 - 2009

- Think Good Thoughts For Feel-Good Librarian - 2007

- My Code4Lib Keynote - 2007

- Reviews Resumed - 2006

- The Art of the Personal Essay : An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present - 2006

- Steve Lawson's Batch of Feeds for Computers in Libraries - 2006

- Code4Lib Conference Notes Up - 2006

- Treadmill of Craft - 2006

- FRL's Library - 2006

- Media Bloggers Association to the Rescue - 2005

Have you seen what Jamie LaRue is doing in Douglas County Colorado? I’ve only read briefly about it but it looked promising to me as a librarian, a writer, a reader, and a library user.

I should check up on Jamie. His instincts are true North.

KG, I am confused about what is going on in the publishing industry and every time I read something in an effort to understand, I stay confused. In this essay you sound confused, too. What does it mean? Where is it all going? I want somebody to explain it to me.

Michael, it’s what Deep Throat said: follow the money.

I suppose the future is always open, but the the structural factors may well determine the outcome. As Eric Hellman has recently shown, public libraries comprise about 4.6% of publisher revenue and 50% of actual reading. (Hellman’s analysis comes two years after I came to much the same number by another method.) There’s no way this gap is made up either through the “promotional” effect or by libraries serving people who wouldn’t otherwise buy books. (A LJ study recently found that top patrons were wealthier than the national average.) Hard as it is to hear, libraries are a hole in publishers’ bucket. Their decision to withhold library ebook sales, at least until per-lend prices rise to close to sale prices, is entirely rational. No amount of complaint or of conversation is going to make this basic, deep driver go away.

There are three solutions here, which you may perhaps file under “magical thinking.”

1. Don’t get too heavy into ebooks. For economic reasons some ebooks will stay cheap. Most won’t. Don’t get sucked into promising something you can’t provide. And don’t hollow out your print collections–as it now happening–to do it.

2. Start adjusting to considerably higher acquisition budgets–at least 5x and probably closer to 10x. Libraries are, of course, underfunded, but acquisitions are generally relatively small. For libraries to give publishers what they’re going to demand, libraries have to anticipate ebook rental costs taking up the lion’s share of their budgets.

3. Lobby Congress for a legislative solution. This solution would (i) Require publishers to sell ebooks to libraries, (ii) Establish reasonable–but, from today’s perspective–steep per-rental fees to publishers.

For “generally relatively small” read “a relatively small percentage of the overall budget.”

Tim, 2 and perhaps 3 have some validity.

Note that publishers have had their eyes on libraries for a long time. A pioneering librarian, Marvin Scilken, led the charge to expose imbalance in bookstore/library pricing decades ago, which resulted in an agreement on library pricing that no doubt has stuck in publishers’ craws ever since. (See his Wikipedia bio, cf. the section “1966 Senate Hearing on the Price Fixing of Library Books.”) Depending on who is in office, there would have to be some similar sympathy these days. Studying those hearings and their arguments might be useful. (Just like studying librarians of yore is valuable. Definitely at least one entire week in my Fantasy Library Class.)

the public library will not be about collecting and warehousing things, like it is now. as far as information and things to read, the PL will be about hunting, gathering, and licensing access “just in time” as needed, in almost real time. But the library as place, as program, as convenor and conveyor, as bridge from known to unknown, will continue to be needed and used.

Publishers will take a page from the game model. Give the game away for free but start charging once you get past level five. Or chapter five.

And fairly soon this will all be moot anyway as publishers themselves are cut out of the picture, and authors go directly from their own keyboards to their readers. Libraries will be dealing directly with copyright holders or will be going through a rights clearinghouse, much as we pay a flat fee for public performance rights thru Movie Licensing companies today.

In response to Tim (hi, Tim!) one thing that gets lost when publishers try to model the impact of libraries on their market is whether or not the populace, which currently get 50% of their reading material at the library, will then purchase that reading material if deprived of free reading. (It seems pretty clear to me the answer is “hell no.”) Further, it’s difficult to assign metrics to how much the public library system contributes to creating a sizable reading public. I strongly believe that without libraries the installed customer base upon which publishers rely would be much, much smaller. I have never seen a figure for that, and I have no idea what it might be, but I think it’s an important variable that is almost always missing from publishers’ equations. Librarians are beginning to argue that we aid discovery – meaning people become aware of certain books and then those books sell better (cf The Help, a sleeper until libraries promoted it) but more importantly I think is that without libraries far fewer people would read for entertainment and the total market for the book product would be relatively tiny. Our culture would b deeply impoverished, too, not that it matters in these business discussions.

KGS, thanks for the kind words and for the info on 1966 – I know absolutely nothing about this and am eager to make up for my ignorance. Fascinating! Also, can I take your fantasy class?

Barbara, I think we should co-teach that fantasy class. I bet we both have a list!

Also, you said (again, so succinctly) exactly what I was trying to dig out of my brain.

Marvin Scilkin himself told me about his efforts in this area back in the 1990s. He was one heck of a librarian. I still miss him.

Jean, interesting predictions (and I agree on the library-as-place). The rights clearinghouse is already happening in higher ed for scholarly publications.

[…] Google: “don’t be evil†does not translate into “do be good.†What is to be done?”Via freerangelibrarian.com Like this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

Publishers are always going to follow the money because they are businesses. (Business with very low profit margins, BTW.)Who can blame them for looking at ebooks as possible cash cows? Production and shipping costs, which are huge parts of the cost of making books, are eliminated.

An interesting idea I have seen around licensing ebooks is unglue.it, still in alpha, where libraries contribute money, Kickstarter style, to buy creative commons ebook rights by title (or group of titles). Publishers and authors get paid and the ebook is “freed.”

Hi Karen! Wonderful writing as always.

As I see it, the problem is that public librarians sacrificed ownership, discounts and the user experience virtually (hah) without a struggle.

What my library, Douglas County Libraries, has done is to build our own econtent management system. It has four components: Vufind (open source discovery and local cloud delivery), Adobe Content Server (industry standard DRM system), and MySQL (to store public domain and Creative Commons). See also: http://jaslarue.blogspot.com/2012/01/dear-publishing-partner.html (to see how our system works), and http://jaslarue.blogspot.com/2012/01/statement-of-common-understanding-for.html (to see our proposal for a new “license” that makes it possible for us to help authors find readers and make money, without requiring us all to pay for lengthy and restrictive contracts).

We don’t have to wait for vendors to save us. And I think we need to start thinking more about authors than about publishers. Public libraries can (and do) add extraordinary value to the content distribution chain. And it may be time for us to BECOME publishers.

Thanks for covering this, I think it’s really really important.

To begin with, I think at least libraries need to start educating their patrons. Or rather warning, sounding the alarm. This is a looming crisis in, okay, reading.

I wonder why the ALA is not working in education/lobbying on this front? Is that not what they’re for? So maybe ALA members need to start asking that.

Although the ALA might be likely to make this about ‘libraries’, not about ‘reading’. I hear you on messaging as ‘not just about libraries’, although I’m not sure how to do that effective, maybe because from my perspective a LOT of it really is about libraries.

Jean writes:

> the public library will not be about collecting and warehousing things, like it is now. as far as information and things to read, the PL will be about hunting, gathering, and licensing access “just in time†as needed, in almost real time.

What you are saying is the public library will give up it’s mission of public subsidy for providing information to people who couldn’t afford it on their own. We’ll help you find free things, and we’ll help you find things to buy. You want to buy it, hope you can afford it.

That would be a shame.

Tim suggests libraries simply don’t buy ebooks. But it looks like reader preferences are shifting toward ebooks; assuming that trend keeps up, that’s saying the same thing, we’ll help you find information and recreational reading that we pay for for you, you don’t need to pay for it individually — but only on old crusty print that you don’t actually want. (Note, personally I LOVE print books, and do not particular like reading ebooks, but it’s not about me.)

It’s not JUST about public libraries. Academic libraries too (many of which are already heavy into ebooks. DRM-protected, hard-to-use, expensive, ebooks), are based on the idea that individual students and scholars all have access to materials on an equal basis, materials paid for collectively by the institution. Giving up on providing content is giving up on this, “you want it, you buy it, with your personal money, your grant funds, your departmental budget, whatever.”

In general, yet another example of the war of capitalism on any collective purchasing or ownership. You aren’t _allowed_ to own those books as a community anymore (literal municipal community, academic community) — every person that wants it has to buy it and pay for it individually and not share it, and those with more money get more access. Maybe ‘charity’ can make up the gap.

[…] Via K.G. Schneider […]

I’m just a reader, but wanted to comment about this. I think Jamie’s statement is great. The libraries should go to the writers, go around the publishers, just as the journalists are self publishing.

Temporary solution:

Can I as a reader donate my e-book to the library. Amazon says I can read it as many times as I like, could I offer it to others to read as well? Create a site, where individuals can loan out the e-books that they purchased. I do loan out my kindle occasionally, but would not do that for strangers, even in my own library community.

[…] Karen Schneider said in her latest post about ebooks, “we need some serious theory at work for us.” We also need more data. I saw so many […]

[…] If librarians fill demand for RH titles, we have to buy fewer books from other publishers… not to mention fewer RH copies. If you’re responding to user demand for the most popular titles, that means more small publishers go on the chopping block. (Adios, Cassoulet!) […]

As a small start while e-book publishers work things out, librarians can direct patrons to public domain e-books, which are cooler than you’d think. I built a website out of my obsession with building my own digital e-library, which is currently pushing 3,000 volumes and which has me reading a wonderful variety of stuff. There’s a meta-search engine that searches carefully selected free e-book sites (only sites that don’t require memberships or software):

Aunt Lee’s Obsessive Meta Search Engine for Free E-Books – http://www.auntlee.com/ebooks/

And I wrote tutorials to get people up to speed as far as I have gotten in the whole e-book thing:

http://www.auntlee.com/ebooks/tutorials.html

[…] digital books means that those will also go out of circulation, just like our physical books do. We have a long way to go for libraries to use ebooks meaningfully—which is likelyimperative to their […]

[…] yet! As Barbara Fister keeps arguing (and as I wrote earlier this year in An ebook and a hard place), shifting the focus from beans to soup (as it were) isn’t an excuse for abandoning our […]

[…] See on freerangelibrarian.com […]